I thought DDT might get your attention. After all, who can forget Rachel Carson's seminal work Silent Spring that first brought the now-banned pesticide DDT to light. But I don't want to talk about chemicals right now, rather a very different type of DDT: Desired Dough Temperature.

Why worry about the temperature of dough?

Well, why sauté onions on the stove at a low temperature or bake muffins in a 350 F oven, or slow-smoke a pork shoulder on the grill at 200 F? Because temperature matters, that's why.

In bread-making, temperature is actually a hidden ingredient, one that can determine the difference between a weak and robust rise of your dough, and which, when manipulated, can actually control the flavor and texture of the final loaf. So yes, temperature really IS an ingredient.

Ideally, in breadmaking (with the usual caveats), you want to rise your dough at about 78 F (a pretty normal DDT). And here are the caveats: In the winter (like now) you might want to begin somewhat warmer, so the yeast get a chance to get going before the cool temperature of your home kitchen slows them down; or before you place the dough into a really cool (42-55 F) environment to really reduce yeast activity and get a long rise. And to me, a long rise means superior flavor and texture.

So how do you get the right DDT? By measuring the temperature of your kitchen, the flour, and water (I'll leave out the complexities of a sourdough starter and mixer here). If you lived in an ideal 78 F degree world, the temperature of those three ingredients, 78 (flour) + 78 (kitchen temp) + 78 (water) would equal 234 if added up. But my kitchen isn't ideal.

Recently the kitchen was 71.7 F and my flour measured 68.4 F. So what do I do to get a final dough of 78 F? I alter the temperature of the one ingredient I can control: water. I take the desired total of the three variables, or 234, and subtract the temperature of the kitchen and flour to figure out what the water should be. So: 234 (total) - 68.4 (flour) - 71.7 (kitchen) = 93.9 (water).

This tells me that if I add 94 F water to my initial mix, I should end up with a dough at around 78 F. That's what I did and got pretty close, ending up with 78.5 F in the dough pictured above.

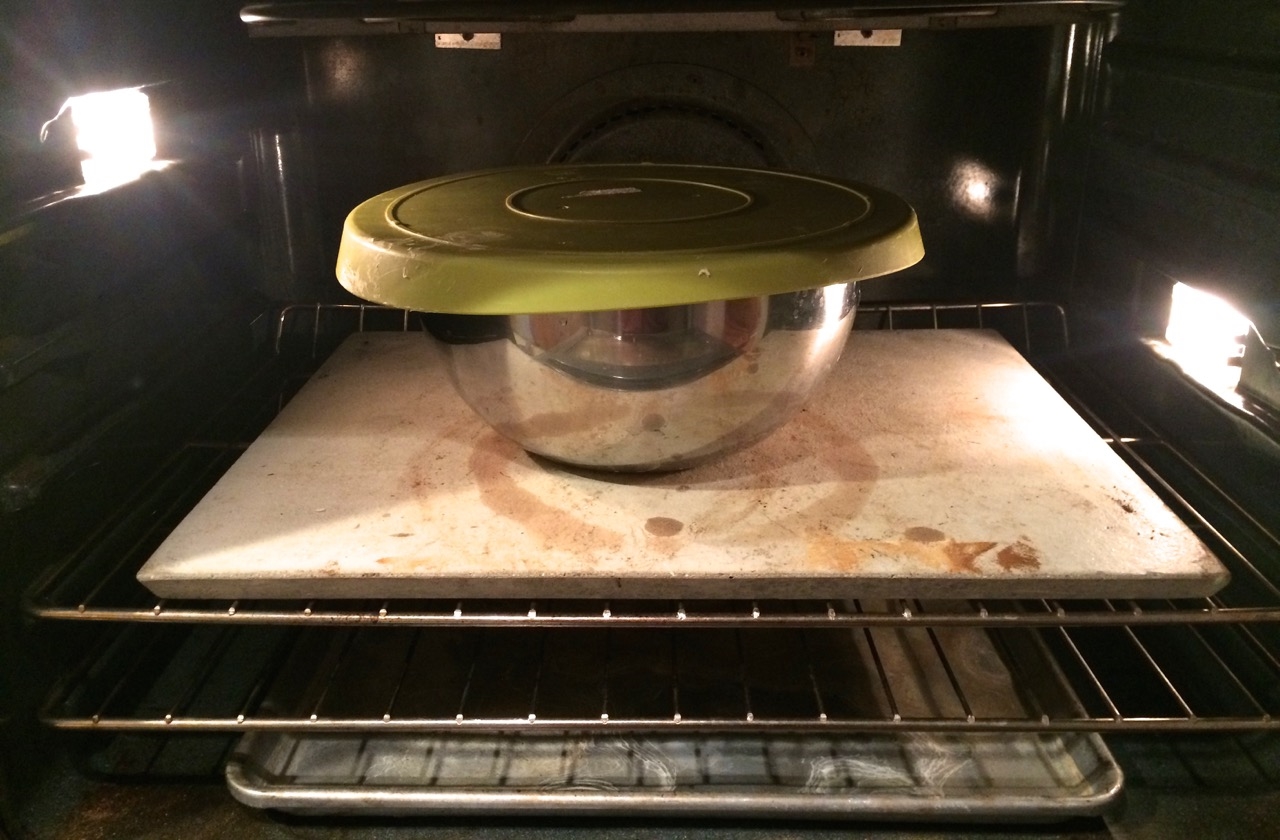

Generally, I know that in the winter I should mix my dough with water that's about 90 F. Then, because my kitchen's relatively cool, I also rise the dough in the oven, heated by the oven lights. If your kitchen is really cool, turn on the oven for 1 minute (not longer!). It makes a huge difference. But don't forget to turn the oven off, and also MAKE SURE you remove the dough before preheating the oven to bake.

Another tip for baking in winter: Before you mix your dough with the warm water, remove a tablespoon or two and proof your dry yeast in it for 5 minutes. You don't need to proof instant (or bread machine) yeast, but I find in the winter, yeast love a warm water bath before they go to work fermenting your dough.

After my dough has been folded several times and risen for about 1-1/2 hours, I then put it in a cool closet in the basement to get a nice, long 24 rise to really develop the flavor.

It was quite cold last night, so when I removed the dough this morning it was only 43 F. You can use this long-fermentation technique up to temperatures of around 60 F. Much more than that and the dough can overferment.

Here's a final tip: If your kitchen is really cold, like 65 F, and your bread is hardly rising at all, put a pot of water on the stove and bring it to a rolling boil. Let it boil away and your kitchen should warm up fairly quickly.

For more on DDT (with the added variable of a mixer, which can also heat up dough), see this post at King Arthur Flour. For another take, see this post on Wild Yeast blog or this one on Farine.